I want to encourage you to embrace (or create) wild spaces in your garden. What do I mean by ‘wild space’? Well, the garden above was planted on purpose to be a bit messy and out of control. This is one of my pollinator gardens, in which I have strategically placed perennials (which return every year), but I also incorporate lots of annual seed. About four times a year, I pull out anything dead, and seed more stuff for the coming season.

I just pulled a bunch of borage and phacelia out of this space, but the poppies and echium and lupine are still flowering, and I want them to self-seed for next year; I’ll leave them a bit longer. Meanwhile, I mixed some cosmos, zinnia, and tithonia seeds with some rotted manure and scattered this in the bare spaces between the still-flowering spring plants. While I was working, I saw all kinds of life. Butterflies (mostly gulf fritillaries, but also a swallowtail and a painted lady), birds (towhees, chickadees, finches, sparrows, hummingbirds, and wrens) and lizards galore (Western fence lizards and alligator lizards). None of these creatures would stand still for photography. But I also wondered how many insects I would see in the space of ten minutes, so I timed myself and took as many pictures as I could within that time frame, in this particular garden. Here’s what I saw.

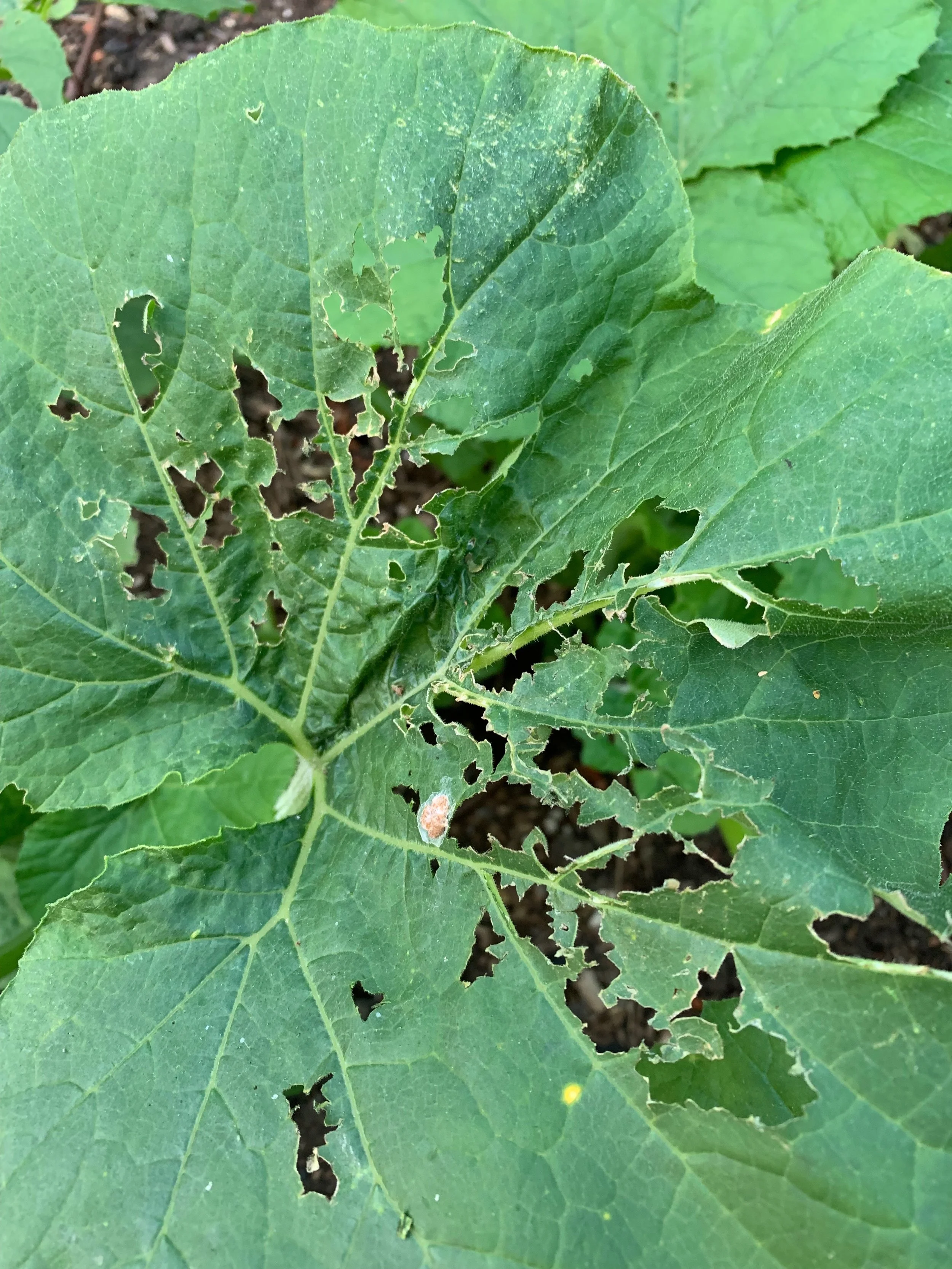

Now, you may have looked at some of these insects and said “I don’t want that one, I don’t want that one, I don’t want THAT one,” and of course some of these are insects we would consider ‘bad’ for the garden or home. But nature doesn’t look at things that way. Nature wants balance. Nature wants diversity. All of these creatures have a purpose and if we have them around, we are better off in the long run.

Messy spaces (or wild spaces, as I like to call them, it sounds so much more deliberate) aren’t just good in the obvious ways. Leaf and bark litter also provide habitat for all kinds of beetles and caterpillars. Bare soil underneath plants provides homes for ground-nesting native bees. Holes in old sticks provide more nests for bees and beetles. Dead flowers decompose on the soil, allowing nutrients to be recycled to the plants. Soil creatures feed on detritus, providing that all-important poop loop in the soil. Fungi creeps in the spaces in soil and in litter, forming connections between plants. The soil is shaded by all the biomass, keeping it moist and cool.

I found a scientific study that encourages wild spaces especially in urban gardens, not only to provide habitat for wildlife, but to help with our health and happiness, too. “When designed with nature in mind, urban gardens can support a high level of plant and animal biodiversity that may lure people back into nature…. more vegetatively complex elements of the environment are more intriguing and challenging to understand than simple ones. As such, complex elements can transport people into a new world, lengthen time spent in the garden interacting with nature, and thereby promote lifelong connections to nature.” I think that’s pretty cool. I know it’s true for me, that I’ll go out to add seeds or pick a bouquet for the house, and I end up standing in the garden for an hour, just watching what’s happening there. I’ll be folding laundry in my bedroom, which looks out on this particular garden, and I’ll see walkers/joggers stop at the pollinator garden and just stare. They’ve completely forgotten their walk. It’s mesmerizing, and it’s all from letting the space get a little wild. Stuff HAPPENS there. Life happens there.

If this interests you, you might check out this article by the Nature Conservancy. It details why a messy (read; wild) garden is a boon to wildlife in any season.