As a teacher, I’ve learned that if I state a claim during a lecture, at least one student is going to question it. I’ll get asked, “What’s your source?” or, “What’s the history behind that information?” or, “What’s the data that backs that up?” I have learned to love those questions, because it has made me a better teacher. I don’t dare write a lecture without exploring, and citing, every angle of every claim I make. This is important work and I’m glad to do it; especially because science frequently changes as more experiments are conducted. After all, it does no one any good to learn old science.

But all of us have ideas about gardening that we’ve heard so often that we take them for fact, whether they are or not. Things like:

Putting eggshells around your plants will protect them from snails (1)

Putting a layer of rock in the bottom of a container will increase drainage (2)

Giving plants a lot of space will quell any competition for resources (3)

Gathering up leaves and other plant matter from under plants will help them grow better (4)

You get the drift.

So, when a student recently said to a class, “Plant comfrey! The deep taproot will bring minerals up from the lower levels of your soil!” my inner alarm went off. I hear this all the time. Where did this idea come from? Is it true?

Comfrey, and other plants like nettles, are widely known as ‘biodynamic accumulators.’ There is no definition for the term because it hasn’t actually been defined yet. It came to prominence in the Permaculture world, as part of ‘plant guilds’ - that is, plants that are placed near each other to provide different benefits to the whole. For example, you might plant a fruit tree, and beneath it place a leguminous bush to provide nitrogen, chives to repel insects, and yarrow to provide biomass for mulch. Comfrey is often included in these guilds for its oft-lauded ability to ‘bring up nutrients,’ whatever that means.

Wait, what DOES that mean?

Well, all plants bring up nutrients, right? The nutrients in the soil are dissolved in the soil water and become the soil solution, which is where plants get the nutrients they need for growth.

How do roots form? When seeds germinate, they form a primary root from the radicle of the embryonic tissue. This helps the plant establish, so that it can unfurl its seed leaves (or ‘cotyledon’ leaves) and begin to photosynthesize. Once the plant is established, it usually forms one of two root systems, depending on what kind of plant it is - a tap root or fibrous root systems. Tap roots have a central root with little side roots coming off of it. The purpose is to anchor the plant in the ground and/or to act as a storage place for nutrients (think of a carrot). The fibrous root system has lots of adventitious roots that move across a wide area to find more surface pockets of nutrients, and cannot store nutrients long term. Confusingly, a very established fibrous root system can also act as an anchor for the plant (think of corn).

image credit: Zassou Garden

We could get much deeper into the weeds here (no pun intended) but I want to keep it simple so we get to the point of this post. Quite simply, plants have adapted different approaches for their needs, but all of these different kinds of systems (whether tap or fibrous) additionally have fine hairs which gather the moisture and nutrients. These fine root hairs will take up whatever is available, in whatever location they happen to grow.

So that means that the roots, wherever they are, whatever kind they are, are taking up nutrients. I suppose, then, depending on the kind of soil you have, there could be different nutrients in different levels. Perhaps you have a very shallow top soil that is depleted in nutrients; it might be good in this case to include deep-rooted plants in your garden to make those subsoil nutrients (minerals from rock, mostly) available. Most tap roots develop a greater number of associations with fungal networks, which break down the rocks at that lower level, so it makes sense that these deeper tap roots are finding different minerals and nutrients. Shallow roots, however, are getting more nutrients from the top layer of organic matter, whatever is available from rotting plant material on top of the soil, as well as from the biological ‘poop loop’ happening with the little creatures who live in the soil.

So yeah: Deeper roots bring up different nutrients. That part is true. But do you need a special plant, like comfrey, to act as this biodynamic accumulator? Is comfrey the only option for this? Most folks are using comfrey as a nutritive mulch; they grow the plant to bring up large amounts of nutrients which are then stored in the leaves (they claim - which again sounds the alarm - doesn’t a tap root store the nutrients in that large root, like a carrot?), and then they chop the leaves, lay them down as mulch, and those nutrients are then brought into the top layer of soil, for the fibrous roots to ‘mine’ for nutrients. At least, I think that’s what the gardeners who buy into the whole ‘accumulator theory’ are doing. Of course, all mulches eventually break down, whether it’s straw or wood chips or sawdust or grass clippings or comfrey leaves. And in that process, they feed the microbial life in the soil, which then poop out the nutrients in a form that is available for the plants (and is taken up by roots). The question then becomes: Do comfrey leaves provide more nutrients as a mulch than any other plant matter?

Well! Turns out there has been a recent study on exactly that question. The study used USDA’s ethnobotanical and phytochemical database to compile peer-reviewed nutrient concentration data across thousands of plant species. They set a threshold of 200% of average for a plant to be called a ‘dynamic accumulator.’ What they found is 340 plant species that showed nutrient concentrations high enough to qualify. This is impressive (plants are always so surprising, aren’t they, in so many wonderful ways?), but what’s very interesting is which, and how many different, nutrients the plants accumulate. The scientists compiled all the data into an online tool called Dynamic accumulator database and USDA Analysis. Here you can see which plants ‘brought up’ which nutrients and in what concentrations.

The next step in the study was to choose six promising species to trial for two years at a community farm. They chose dandelion, lambsquarters, red clover, redroot amaranth, Russian comfrey, and stinging nettle. They wanted to use these plants in different applications, such as liquid fertilizer and mulch production. Here are their key findings (this is a direct quote from the study):

- Plant tissue nutrient concentrations are tied to soil nutrient concentration. Dynamic accumulators are well-suited to extract specific nutrients from fertile soil, but they aren’t going to create nutrition that isn’t there. Therefore, dynamic accumulators should be regarded as one useful part of a larger nutrient management plan.

- That said, even when grown in poor, unamended soil, lambsquarters surpassed the dynamic accumulator threshold for potassium, and comfrey surpassed the threshold for both potassium and silicon.

- Previous studies have shown stinging nettle to accumulate calcium at concentrations above the thresholds. These new findings show that not only does it accumulate a lot of calcium, but it also has a high nutrient carryover rate, resulting in calcium-rich liquid fertilizer and mulches.

So there you go: Biodynamic accumulators are a real thing, and comfrey is certainly one of them. But, one must consider: Does the soil even need these particular nutrients? For instance, much of the Bay Area already has plenty of calcium in the soil. In this case, a dynamic accumulator like stinging nettle, which accumulates high levels of calcium, may not be necessary. Also, none of the six tested in these trials provided a large nitrogen benefit, but I suppose we already know what does provide that, and that is legumes.

I find the first finding the most important: This is only one part of a soil nutrient management plan. Adding plenty of organic matter to your soil, whether comfrey leaves or nettles or wood or straw or manure or chaff or whatever, will feed the microbiology in the soil which will in turn make it bioavailable for our plants. It will also form stable aggregates which will create long-term health. Living roots in the ground, a great diversity of them, will do the same. Eschewing pesticides of all kinds will also help the soil nutrient profile. Lots of soil cover will also prevent evaporation, leading to greater soil moisture and soil health.

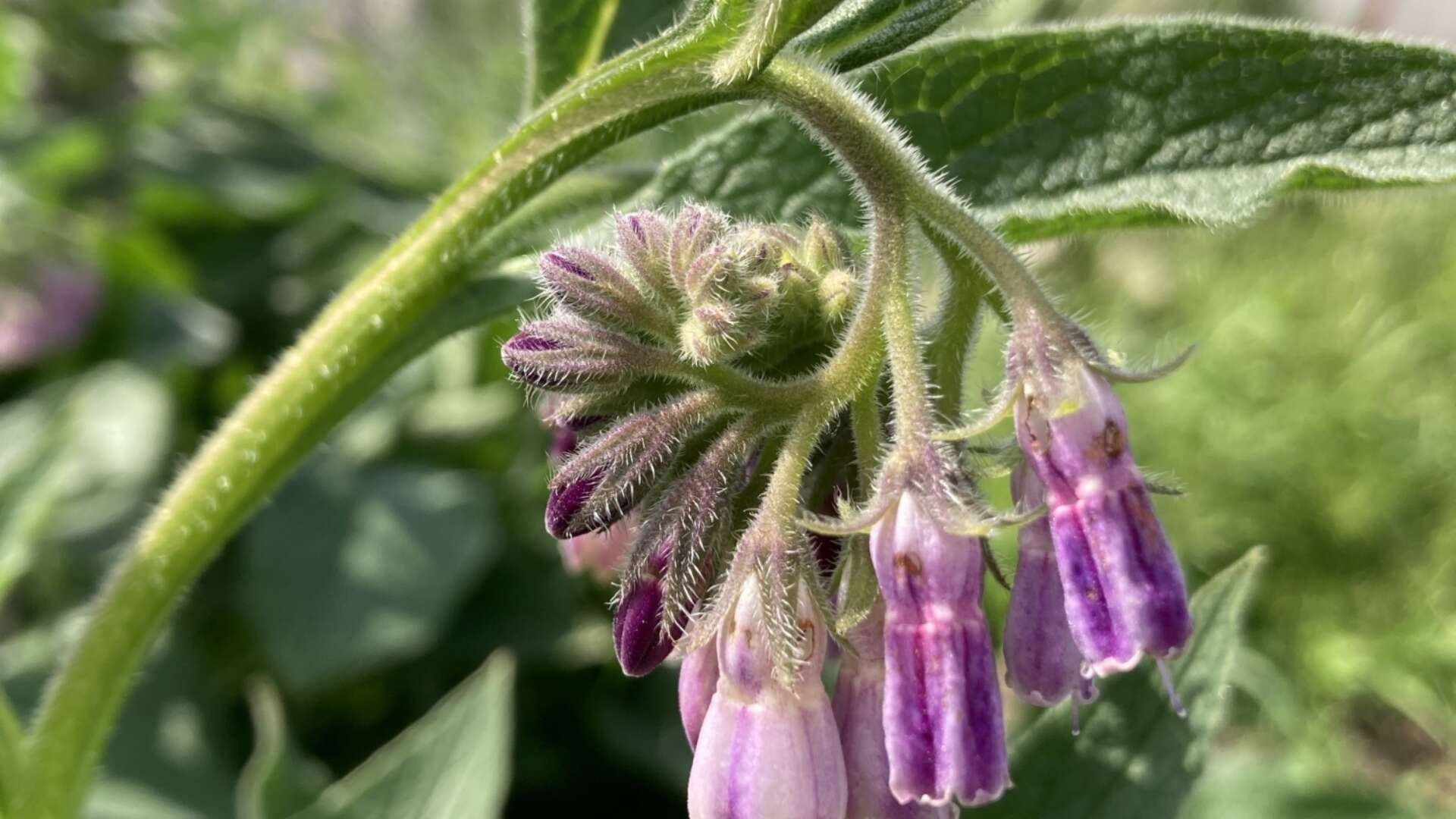

Bottom line: Plant comfrey if you want to. It’s a beautiful plant and as long as you get the Bocking 14 variety, it will be well-behaved in your garden. Insects love it and it thrives as an understory plant for larger species. I myself have just planted 50 root cuttings under the trees in our orchard, if only to provide another living root in the ground, improving the soil profile.